Most people who discovered the app in its early years did so through Facebook and Instagram, where it still regularly ranks among the platforms’ top advertisers. I've decided to document the bizarre things that Wish tries to market to me while unable to target me with personalised ads. At this, it excelled, leveraging Szulczewski’s expertise from his years at Google, where he worked on the tech giant’s advertising algorithms. The company found this swath of the population - and bargain-hunters from higher income brackets, too - on social media and via search, where until fairly recently it spent the vast majority of its marketing budget on targeted advertising. (In both cases, he argued, elites ignored “the invisible half.”) “Despite our metrics, we were told repeatedly and at every stage by Menlo Park investors that they didn’t know anyone that would shop on Wish,” Szulczewski wrote in a 2016 Medium post comparing the startup’s rise to Donald Trump’s surprise presidential victory.

Marketing toward lower-income customers wasn’t part of the original business plan, says Tarek Fahmy, a Wish engineering executive, who joined the company in 2012, but as it saw that customers were prioritizing price above all else, “we recognized that this was a significantly underserved market, especially when it came to e-commerce.” Venture capitalists were initially less convinced. (The company also now has four category-specific apps - Geek, Home, Mama, and Cute - but says they aren’t a significant part of the business.) Its biggest vendors were Chinese wholesalers, and as the company grew, it directed its efforts toward the products that were selling fastest: inexpensive women’s clothing, consumer electronics, jewelry, and accessories - all of which are still among Wish’s top-selling categories. It only started selling merchandise in 2013, for one, before which it more closely resembled Pinterest, offering users the chance to create “wish lists” of products pulled from around the web, along with images they uploaded themselves.īy the time it launched e-commerce, it had 500,000 daily users, Wish’s co-founder and CEO Peter Szulczewski told All Things Digital at the time. Yet compared with other major marketplaces - Amazon (134 million installs last year, for comparison), Alibaba’s AliExpress, eBay - Wish is hardly a household name. Wish sells a wide variety of very cheap, and sometimes odd, items. It was also the world’s most-downloaded e-commerce app of 2018, with 161 million installs globally, according to app analytics firm Sensor Tower. It has raised $1.3 billion since it was founded in 2011, and at its last funding round in 2017, was valued at more than $8.7 billion. Last year, Wish says it saw revenue double from the year prior, to $1.9 billion the company earns money by taking a 15 percent cut of each sale and, to a lesser extent, collecting fees from sellers in exchange for promoting their products.

PAPARAZZI APP FREE

And apparently, even in the age of free one-day shipping, patience is a thing a shockingly large number of people still have. Most delivery estimates range from two to four weeks, giving the marketplace’s vendors time to ship their products from countries like China, Myanmar, and Indonesia.

In exchange for these bargains, Wish demands patience. Most of these prices are presented as 80 or 90 percent off their original price, so it seems like you’re getting a discount. Those AirPod knockoffs? Free with $3 shipping.

PAPARAZZI APP BLUETOOTH

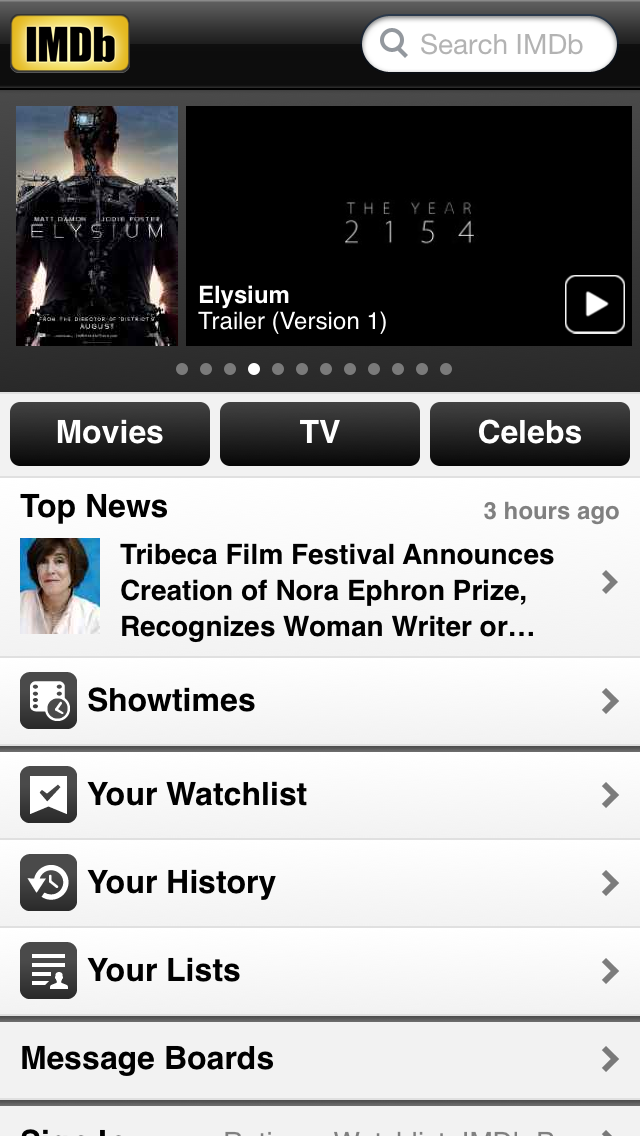

Depending on your shopping proclivities and personal demographics, you may find a collection of Bluetooth headphones, children’s pajamas, cooking utensils, or sex toys - almost all of it sold at outrageously cheap prices: $9 for a set of knives, $5 for a T-shirt. Open the shopping app Wish and you’ll be greeted by a vast array of stuff you don’t need: 12-foot-long pool floaties, whimsical toilet brush holders shaped like cherries and swans, a T-shirt with a photo of the Hanson Brothers above the word “Nirvana,” and at least a few dozen varieties of cord organizers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)